https://montrealgazette.com/news/gerald-matticks-montreals-king-of-coke-dies-at-85

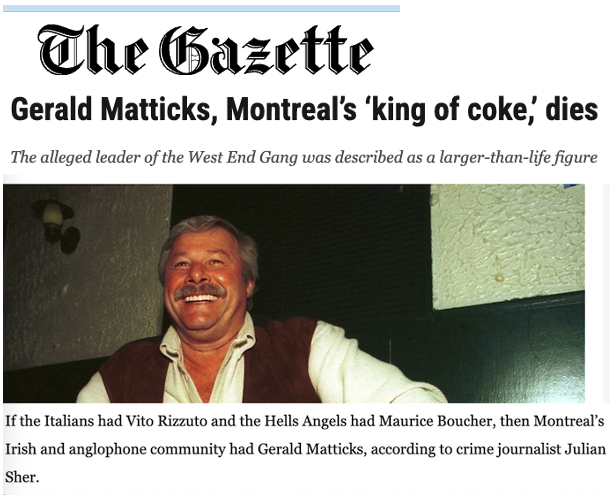

If the Italians had Vito Rizzuto and the Hells Angels had Maurice Boucher, then Montreal’s Irish and anglophone community had Gerald Matticks, according to crime journalist Julian Sher.

He was a “larger-than-life” figure known for giving food to the poor.

And he allegedly led what became famously known as the West End Gang, who were said to have controlled the Port of Montreal. Prosecutors alleged even the Hells Angels depended on him at one point. The bikers called him “the boeuf.”

But to many, he was simply “Big Gerry.”

On Friday, Matticks died at 85, reportedly of natural causes.

His family announced the news on Facebook, prompting an immediate stream of condolences.

“My dad was an amazing person,” Gerry Harris Matticks, his son, wrote to The Gazette. “The most important things to him in life were his kids and making sure he gave back to the poor. He loved Christmas. He loved driving around with Santa handing out toys and food. And he loved his farm.”

Born on July 4, 1940, the youngest of 14 children, Gerald Matticks grew up in what was then known as Goose Village or Village-aux-Oies, a cramped district of Irish Catholic families near the Victoria Bridge. His father drove a horse and buggy for the city.

He reportedly liked to say he had been weighed at birth on a butcher’s scale at the local market and tipped it at 14 pounds.

School then followed, though it was never for him. He quit at age 12, jumping out a window after slapping a teacher who was giving him a belting.

He married at 17 and was the father of four by 21.

He admitted he never learned to read properly and later blamed dyslexia, though there was no formal diagnosis. Instead, he figured he had whatever a friend had. He relied on others to keep ledgers and contracts straight.

“Me, I’ll tell you what I’m good at,” he once said, wagging his finger. “I’m good at telling people what to do.”

Through the 1970s, reports at the time showed a man climbing the underworld. He and his brothers were repeatedly linked to truck hijackings and stolen goods.

A major public inquiry into organized crime in the late 1970s put them on television, casting the Matticks clan as the faces of a loosely organized band of thieves.

They denied everything and were acquitted, but the nickname stuck: the West End Gang.

Drugs would become the real cash cows during the 1980s. And the Irish had long worked the port. Matticks turned that presence into leverage.

In 1984, he became president of the Coopers and Checkers Union at the Port of Montreal, representing workers who handled and verified containers.

That position, investigators later said, effectively made him gatekeeper to what went in and out.

In fact, there was once a strike at the port and only one truck rolled out, said Sher, who went on to direct documentary, The Kings of Coke, about him. The truck was Matticks’. It was allegedly filled with drugs.

His control meant the city’s other major crime figures needed to negotiate with the Irish.

The Matticks Affair

In May 1994, the Sûreté du Québec moved in. The operation was dubbed Project Thor.

Officers arrested Gerald Matticks and his brother Richard along with several associates, seizing documents, cash, gold bars and weapons in raids around Montreal.

Police accused them of importing more than 26 tonnes of hashish through the port.

What followed was a scandal famously known as the Matticks Affair.

A Quebec Court judge eventually stayed the proceedings after it emerged investigators had slipped altered shipping documents into the evidence to give the impression they had been seized at a co-accused’s office, when they were in fact faxes police themselves had received.

It led to the Poitras Commission, a public inquiry that cost about $20 million, which concluded the provincial police force had broken the law and protected its own.

Matticks had claimed his run-ins with police began at 18, with an arrest over a stolen car he said ended with several days of beatings with fists and phone books.

He would later recount what he described as being persecuted by the police to The Gazette’s Lisa Fitterman in a rare interview in 1996.

Fitterman said she had asked his lawyer for an interview following the SQ officers’ trial over the evidence-planting. He reportedly asked if she “was the journalist who smiled a lot in court.”

He invited her to Mickeys, his country-and-western bar in St-Hubert.

Fitterman described in her article the band played heartbreak standards and the air was thick with smoke. The waitresses also seemed to have been hired with Dolly Parton in mind, she added.

That night, he said to her he could put away 40 ounces of gin in a single sitting.

“One is inclined to believe him,” Fitterman wrote.

In the room, she detailed, there was a photo with Youppi! and snapshots with his children and grandchildren. There were aerial images of his South Shore cattle ranch and a postcard of sunbathers in thong bikinis. There was even a still of a leather-jacketed Marlon Brando from On the Waterfront.

“I’m a fast talker and I talk rough,” he told her, “but that’s not my meaning, if you know what I mean.”

Peak power and a fall

The failed hashish case did little to slow his ascent. In fact, the years that followed, from 1994 to 2001, may have been his height.

Evidence presented in biker trials suggested he had become the main supplier of hashish and a key facilitator of cocaine shipments for the Hells Angels’ elite Nomads chapter. Millions of dollars’ worth of drugs were believed to have moved through containers he could have waved through the port.

And his loyalty to his brother remained fierce.

In 1997, after Richard was sentenced in a separate case, Matticks emerged from court calling the process a sham and insisting his brother was being railroaded.

“The only coke my brother touches is Diet Coke,” he reportedly said.

In March 2001, Matticks was ultimately arrested with more than 120 bikers and associates in Operation Printemps 2001 in the largest anti-gang sweep in Quebec history.

The next year, in exchange for a guarantee he would not be extradited to the United States, he pleaded guilty to being a major supplier to the Hells. Prosecutors said 33,000-something kilograms of hashish and 260 kilograms of cocaine had passed through the port with his help. He wound up receiving a 12-year sentence.

Then, at a 2009 parole hearing, he dropped the pretence.

“I was the big guy in there,” he said of the port. “Without me, it wouldn’t have happened. I was the key man.”

Though, throughout, stories of his generosity persisted.

After serving his time, he appeared to retreat to his farm, out of the game.

His older brother Richard would pass away in 2015 at age 80.

Unlike many men of the crime underworld, the pair did not die in a prison cell or in a gangland hit.

“They had no international ambitions,” Sher said. “They were local boys who were content to be kings of coke in Montreal.”

Article content

With files from The Gazette’s Lisa Fitterman and Paul Cherry.

Article content